(Following is the third and final installment in the story of West Union’s Grover Swearingen and his recollections of his service in World War II.)

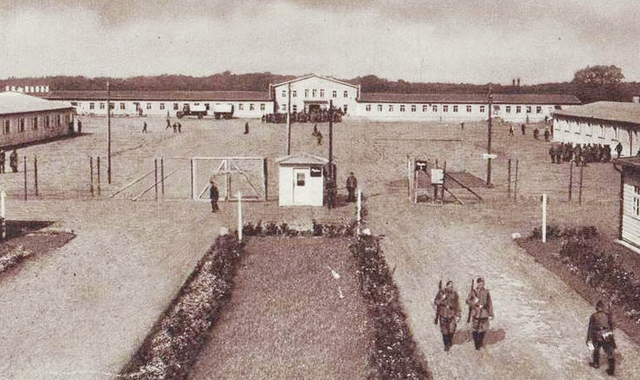

The German winter of 1945 was among the coldest of the 20th century. Blizzards and sub zero temperatures persisted from January through March. Grover Swearingen and his fellow prisoners were being held in the German POW camp at Gross Tychow, Poland, where they were struggling to survive starvation and the bitter unrelenting cold. Assigned to a barracks without bunks, the men slept four to a pallet on the wooden floor sharing their blankets to keep warm. Not until the last week in January were bunks constructed in their barracks.

At the same time, the distant sound of Russian artillery was growing closer and louder with every passing day. The POW’s had no way of knowing that Adolf Hitler had issued orders the previous summer that called for the evacuation of prisoners-of-war to the rear. Those orders prolonged the war for the POW’s, subjecting them to the severest hardships: starvation, exposure, injury, disease, and death.

In accordance with Hitler’s orders, on Feb. 6 the POW’s in the camp were given Red Cross parcels and told to prepare for a three-day march. Some 8,000 prisoners set out from the camp. The men were allowed to carry as much as they could. The three-day march would last 86 days.

Swearingen was a smart, practical kid off the farm. He may have lacked the signature street smarts of the urban young men he met, but he didn’t lack intelligence or fortitude, which allowed him to survive one of the most harrowing historical events in modern history, the Death March.

The prisoners were forced to walk westward, with much zigzagging to avoid the fast-moving Russian army.

“The temperature was fifteen above zero and there was about 11 inches of snow on the ground,” Swearingen recalled, “We started out and marched all day and at the end of the day we were put up in a barn. Some of the boys had blisters on the bottom of their feet (from walking) and the doctor took a pair of scissors and cut them off. He had no medication to put on the blisters and the boys had to walk on them the next day. Bob Brown and I were in better shape. We were used to walking around the camp so our feet were okay.”

The conditions in the camp had not prepared the POW’s for what they were about to face. Half starved, lice-ridden, sick and weak, without proper winter clothing, they were forced to march 20 to 40 kilometers every day (12 to 25 miles). Leaving their POW camp in Gross Tychow, Swearingen and the others were forced to walk 500 miles across Germany through blizzard conditions. They walked without destination, possessing little of the barest necessities: food, clothing, shelter, and proper medical care. Hundreds would die along the way from exposure, disease and starvation.

They stopped only to sleep in barns, churches, factories, abandoned buildings, and fields. “We marched 40 kilometers and were herded into a field to sleep,” said Swearingen. “It was raining and about 32 degrees, we were given a pint of thin barley soup at lunch and that was all the food we had. We tried to sleep but our blankets soon were soaked. The guards let us build a fire and we huddled around it to keep warm.”

Unsanitary conditions and starvation left the POW’s vulnerable to disease. Typhus was spread by body lice, and dysentery was very common. The debilitating disease spread like a plague among the men. Prisoners suffered the degradation of soiling themselves while being force-marched. “Some of the prisoners ate charcoal to help with the dysentery,” Swearingen said. “I guess God was with me because I was never sick and never had a cold all the time I was on the march.”

Prisoners who did not have warm clothing (the Germans did not provide winter clothing for POW’s) suffered from frostbite which frequently led to fatal gangrene.

Prisoners who were lucky enough to have boots usually chose not to remove them. If they left them on trench foot could result, but if they took them off it was impossible to get them back on over swollen feet, or the boots could freeze, or be stolen.

“Although I had wet feet and wet clothes, I never took my shoes off all the time I was on the March. Forty-five years later I learned I have damaged nerves in my feet and legs caused by the cold. I could never understand why my feet were always so cold and had no feeling in them,” Swearingen added.

There were also abundant random acts of kindness during the march. “We tried to keep three or four in a group so we could help each other along the way.” Swearingen described. “They had wagons for the sick and weak that couldn’t walk, but sometimes if a prisoner was too weak to walk, they’d fall out out along the road. A guard would stay with him. Shortly you’d hear a shot fired and the guard would catch back up with the group. What happened to the prisoner only God and the guard knew.”

Because there was so little food the prisoners were forced to scavenge for whatever they could find.

“We were permitted to go with the guards to find potatoes and other things we could cook over the fires they let us build,” Swearingen explained, “When we arrived at one particular farm there were at least 200 chickens. We stayed there and when we left two days later, you couldn’t find a chicken anywhere. One of the boys had a long coat and he would walk up to a chicken, squat down and get the chicken, then wring its neck. He’d come around and ask if any one wanted a chicken. You could put the chicken in the bottom of a pot with potatoes on top, and half cook it and then eat it, but we had to be careful not to let the guards know.”

As the harsh winter came to an end and suffering from the numbing cold abated, many of the POW’s who carried spare clothing and preserved food on sledges began discarding their supplies. Their route became littered with items that couldn’t be carried. “ Some of the boys had taken all that they could carry,” Swearingen wrote in his memoirs. “It was all discarded along the way. Bob and I wrapped our food up in our blankets and carried them slung over our shoulders.”

On the last day of March, the 54th day of the brutal trek, Swearingen arrived at Stalag 11B in Fallenbastel, Germany. “Four hundred of us slept in a small chapel that night,” he said. The treatment was a torturous repetition of previous camps, with the exception of food, of which there was virtually none. Nor were there beds or bedding in the buildings.

The prisoners, and the Germans as well, knew liberation was close at hand. The sounds of the approaching American artillery grew louder with each passing day. The POW’s had been in this camp for about a week when Swearingen and the other prisoners from his camp were taken out on their final march, this time to the east.

“On April 8 we were evacuated in a downpour of rain. The allied armies were closing fast,” Swearingen recalled. This final march lasted approximately three weeks, and was just as harsh as the previous march except for the treatment by the Germans, which was somewhat improved. There was still little or no food, and the pace was much slower, advancing only 3-5 miles a day.

“We marched back over the route we’d taken. I celebrated my 21st birthday crossing the Elbe River going east. We were buzzed by a P-51 Mustang fighter plane. After we crossed the river, the Mustang sank the ferry,” Swearingen said.

On the morning of May 2, 1945 the British arrived and liberated the camp. “We wondered why the guards had thrown down their guns that morning,” Swearingen said. “A British officer walked into the barn yard and told us to take care of any guards who’d given us trouble a

nd several POW’s went after the SS officer who’d given us such a hard time.”

They were free. The airmen began walking west. After a short distance Swearingen and a few others confiscated a farmer’s truck and several of them were able to ride the last 20 kilometers to the British camp. “We were given some food, at last, and told to sleep in a barn. The next morning, they put us in a room, took our clothes, and burned them, lice and all. We were deloused and given new British uniforms.”

From there Swearingen and the others traveled back to Fallenbostal, then onto Namur, Belgium where they were turned over to the American army. “We received an army uniform and the next day we were sent to St. Vallery, France. We stayed in a tent city called Lucky Strike, but I didn’t mind because we had good food and a good cot to sleep on.”

The prisoners were put on diets to rebuild their weight and strength. “They wouldn’t give us very much food at one time, but they let us have all the egg nog we could drink to put a little weight on our bones. I weighed 98 pounds.”

By the end of the march most of the prisoners had lost a third of their pre-war weight. While at camp Lucky Strike Swearingen was briefly reunited with his crew from the B-17 bomber. “They were shipping us out every day. It finally came my turn and I was put on a liberty ship that had returned from taking a load of German prisoners to America. They didn’t unload them, but just turned around and brought them back.”

Swearingen would spend 15 days on board the ship as it sailed across the Atlantic toward America. “We had chicken about every day,” he said, but after what I’d experienced eating half-cooked chicken, I turned it down. I’d rather have been hungry than try to eat it. I still can’t eat chicken to this day, the more I chew it, the bigger it gets.”

Back in the states Swearingen was sent first to Camp Miles Standish in Boston, then by train to Camp Atterbury, Indiana. He was granted a thirty day pass to go home. “I went by train to Columbus, then took a bus to Portsmouth. I called home and told them I was on my way and would be there on the next bus. It was the first time my family had heard from me since I’d been shot down.”

Like millions of young American men and women who had fought so bravely, and endured so much, he was returning home to a grateful family.

“I was met by my dad, my mother, my brother and his family and it was sure good to see them.”

After the war, Grover chose to settle in Adams County where he worked as an accountant, married, and became the father of two children.

Many years after returning home, he wrote about his experiences as a B-17 radio operator, a prisoner-of-war, and a survivor of the death march. He has also spent many years visiting local high schools and sharing his war time experiences with students.

Now, at 93, he says, “It was all a long time ago, and I’m just grateful that I made it out alive.”